You might have heard of AVX to SSE transition penalties, or VEX encoding, or seen some assembly with a lot of "v"s in front of instructions and been mildly confused by it. Hopefully, this post can help clear these concepts up - what they are, why they matter to you (or don't, hopefully), and why they are significant.

A brief primer on SSE and AVX

Your CPU has a cool ability to do a thing called SIMD (Single Instruction Multiple Data) operations. These, as the name suggest, are instructions on your CPU which can perform an operation on multiple pieces of data at once, as opposed to SISD (Single Instruction Single Data). SISD is also known as scalar code, and SIMD as vector code. You'll hear these terms frequently.

An example of SISD is a normal x64 addition:

add eax, ecx

(For the lucky uninitiated few, eax and ecx are x86 32 bit registers. Naming of it isn't important here. And the first register functions as both a destination and a source, so it is equivalent to roughly eax = eax + ecx).

This is a single instruction, and it operates on single data. Yes, it has 2 operands, but they are both part of the operation, so it is a single data stream. An example of SIMD is

paddd xmm1, xmm0

This instruction is Packed ADD Double words - (double words = 32 bit integers). Now we need to introduce xmm registers. There are 16 xmm registers, xmm0-15, on your standard 64 bit SSE CPU. (8 on 32 bit CPUs, but they don't get AVX so they are irrelevant to this article). They work on a seperate part of your CPU, the vector unit, and are awesome. They are 128 bits wide. Which means, in this case, they can fit 4 integers - 128 / 32 == 4. So here, we added each of the 4 ints in xmm0 and xmm1 and wrote them to xmm1 at the same time - even though the instruction is as fast (ok, not exactly, but for most intents and purposes, you can think of it as being as fast). As you can guess, this is super powerful for all sorts of things - processing large amounts of data, working with Vector2/3/4 types in games, and accelerating simple loops. SSE was just the first version that supported these registers, after that we got SSE2, SSE3, SSSE3, SSE4.1, and SSE4.2, which all introduced new instructions for these registers (for example, PADDD is not actually an SSE instruction - it came along with SSE2 (and, yeah, technically MMX, but for your own sanity, ignore MMX)). Then, we got AVX - which upgraded the xmm0-15 registers to ymm0-31. It added 16 new registers, and widedned all the others from 128->256 bits. So now you can do maths on eight 32 bit integers or floats, or four 64 bit integers or doubles, simultaneously. (Now, the whole "as fast as scalar code" mantra takes a hit with AVX - but we'll ignore that for this article). "Wow!", you probably think. "That is awesome". You're right - AVX is very useful. However, as usual, backwards compatibility rears its ugly head. A key thing to remember here - the new ymm registers are just the widened xmm registers - xmm0 is the lower 128 bits of ymm0 - they are intrinsically the same register.

VEX encoding - or "what are the weird 'v's in my assembly??"

VEX encoding is a way of encoding instructions used in vector code (VEX meaning Vector EXtensions). It begins with a VEX prefix, but because the previous encoding had several prefixes and data bytes, it is actually generally no longer than the non-VEX version. VEX was introduced and any instruction which is either AVX specific, or accesses the ymm registers, must use VEX encoding. VEX also allows dest, src0, src1 encoding, rather than destAndSrc0, src1 encoding which is lovely. VEX is the evil monster responsible for the vs in front of your assembly. For example, rewriting the above code to use VEX would be

vpaddd xmm1, xmm1, xmm0

The v literally just means VEX encoded.

Some compilers let you specify the old destAndSrc0, src1 syntax, but it is worth noting this is just syntactic sugar, and is actually encoded as src0, src0, src1 in the isntruction.

Mixing VEX and not VEX

(Note: We ignore xsave and xrstor for simplicity here - but cover them at the bottom, if you need that)

Now, VEX also does something very special in relation to ymm registers. When you perform an 128 bit AVX instruction or VEX encoded SSE instruction - one which begins with the legendary v but operates on xmm registers - it zeroes the upper 128 bits of the ymm register, for performance reasons. This is nice, and known about, and just how it works. No issue here. But what about non-VEX encoded SSE instructions? They have no idea of the existence of the upper 128 bits of the XMM registers they work on. So the CPU has to "save" the upper 128 bits when executing these instructions - it enters a "preserved upper state" and when coming back to 256 bit AVX instructions which write to them (using them as a dest) - note, you can execute 128 bit VEX encoded instructions just fine with a preserved upper state - so the CPU must restore these bits. This is not a trivially cheap operation - Intel give its timing as "several tens of clock cycles for each operation". This isn't great, and means you shouldn't mix them wherever possible. If you have

BigAvxMethod(); // Only AVX instrs

BigSseMethod(); // Old method - only SSE instr

BigAvxMethod2(); // Only AVX instrsyou will get 2 transitions - not great, but not awful, realistically. Both are approximately the length of an xsave instruction.

However, there are ways to avoid this transitions - by only executing old SSE instructions when in a clean upper state (that is, all upper bits are zeroed, and the CPU knows this - that last bit is critical - if they are 0 from some arbitrary operation, the CPU doesn't know the state is clean).

vzeroupper- zeroes the top 128 bits of allymmregisters, and means you are now in a clean upper state, where transitioning has no costvzeroall- zeroes everything from allymmregisters (and by extensionxmmregisters). Also becomes a clean upper stateXRSTOR- For simplicity and relevancy's sake, we will ignore this until the end

vzeroupper has 0 latency (is eliminated at instruction renaming), and so has no performance impact other than code size. However, when executed from a preserved upper state, it has a penalty approximately as long as an xsave.

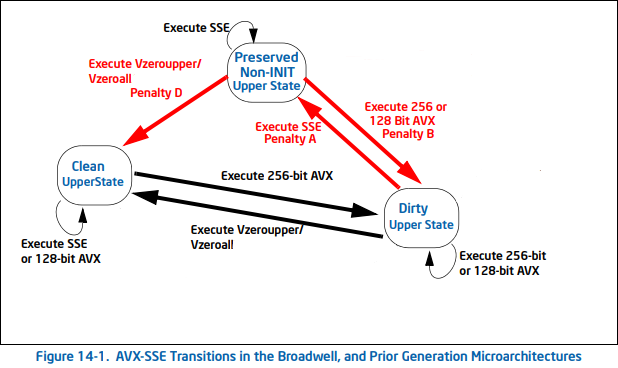

Here is a descriptive image from intel showing the above - black lines represent normal operations, whereas red lines are operations which have penalties. Note that there are only red lines when transitioning - after executing one dirty instruction, and entering the preserved non upper state, all following ones are at regular speed.

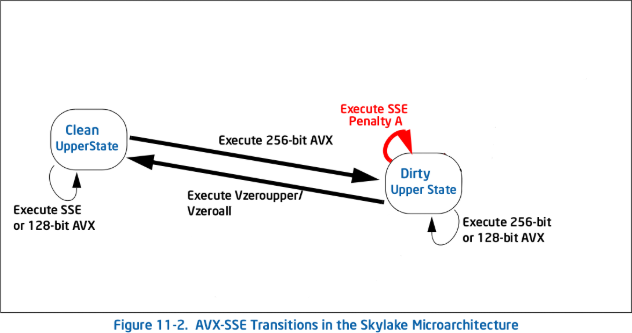

But - this all changed in Skylake and more recent microarchitectures. There is no longer such thing as a preserved upper state - only a clean upper state (from a vzeroupper or vzeroall, and a dirty upper state (after any 256 bit AVX instruction has been operated)). In a clean upper state, you can operate non VEX 128 bit or VEX 128 bit instructions with no penalty. In dirty upper state, you can operate any VEX 128 bit or 256 bit instruction with no penalty.

But what about non VEX instructions in a dirty upper state? What do they do now there is no preserved upper state to enter? The answer is that they simply stay in the dirty state, but have an execution penalty. This means every single non VEX instruction executed in a dirty upper state has a penalty.

However, the penalty is less significant - the per instruction penalty is a new partial register dependency and a blend instruction.

Here is the graph for Skylake+:

Let's look back at the code snippet from earlier:

BigAvxMethod(); // Only AVX instrs

BigSseMethod(); // Old method - only SSE instr

BigAvxMethod2(); // Only AVX instrsHere, every single SSE instr in BigSseMethod will have a non-trivial perf penalty - that is HUGE, and may even be slower than equivalent scalar code. Ideally, we would have access to the source for BigSseMethod and recompile it to use VEX, or get a newer version of the library which used VEX. However, if we don't, then we need to ensure a clean upper state when calling the method. As we see, we need to execute vzeroupper or vzeroall. These are not exposed in high level languages, so we will just use pseudocode for them. vzeroupper is almost always used, unless you wish to zero the xmm registers too for some reason.

BigAvxMethod(); // Only AVX instrs

Asm.VZeroUpper();

BigSseMethod(); // Old method - only SSE instr

BigAvxMethod2(); // Only AVX instrsBut oh no - now the data we need in the upper 128 bits of ymm for BigAvxMethod2 is zeroed, even though we need it. So we need to save and restore this data before and after our vzeroupper and SSE method. Thankfully, there are dedicated instructions to help with this - vextract and vinsert (and their quadrillion AVX512 relatives which we will ignore):

Note: xmm/m128 means it may be an xmm register or a pointer

Extract: Extract 128 bits from the lower half of the second operand if the first bit of imm8 is 0, else if the first bit is 1, from the upper half of the second operand, and write them to the first operand

vextractf128 xmm/m128, ymm, imm8- Floating point variantvextracti128 xmm/m128, ymm, imm8- Integer variant

Insert: Insert 128 bits from the third operand into the lower half of the first operand if the first bit of imm8 is 0, else if the first bit is 1, into the upper half of the first operand

vinsertf128 ymm, ymm, xmm/m128, imm8- Floating point variantvinserti128 ymm, ymm, xmm/m128, imm8- Integer variant

There are no functional differences between the I and F variants, but prefer I for integer vectors and F for float vectors, to keep all execution on the same vector unit (integral or floating point), according to the Intel Optimisation Manual.

So, to preserve ymm0, for example, across a SSE call with a vzeroupper (using DATAPTR to represent an arbitrary stack location to store the data at).

vextractf128 [DATAPTR], ymm0, 1

vzeroupper

call SseFunc

vinsertf128 ymm0, ymm0, [DATAPTR], 1

Note: This probably doesn't actually work on most systems - the low bits of ymm0 are generally volatile (can be edited by a function) - this is purely an example. Consult your system ABI for information on which registers you actually need to save.

So, now our call looks like

BigAvxMethod(); // Only AVX instrs

Asm.SaveRegisters();

Asm.VZeroUpper();

BigSseMethod(); // Old method - only SSE instr

Asm.RestoreRegisters();

BigAvxMethod2(); // Only AVX instrsIn reality, your compiler will handle appropriate zeroing and preserving of registers - however, this knowledge is useful for trying to minimise cases where these transitions occur.

XSAVE and XRSTOR and their relation to preserving upper vector states

This section assumes you know what xsave and xrstor are. If not, see Volume 1 Chapter 13 of the Intel Developer Manuals.

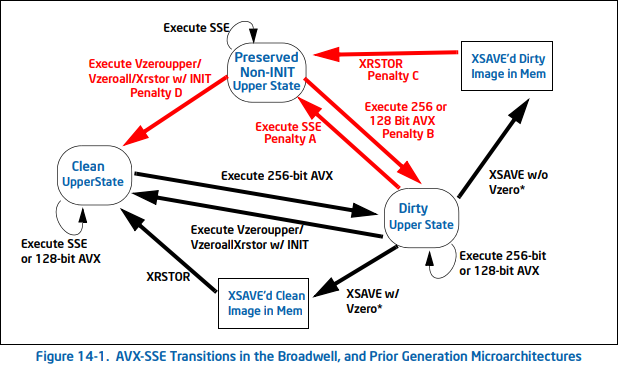

Pre skylake, if you had a clean upper state, saving state, followed by restoring state, results in a clean upper state. Saving with a dirty upper state, and then restoring, results in entering a preserved upper state, and entering this state invokes a one time short penalty during restore, which will become dirty if a VEX encoded instruction is executed, or cleaned by a vzeroupper/vzeroall. Restoring state with AVX state initialized (zeroed) enters a clean state, although if it is from a dirty image or preserved upper state, it invokes a penalty.

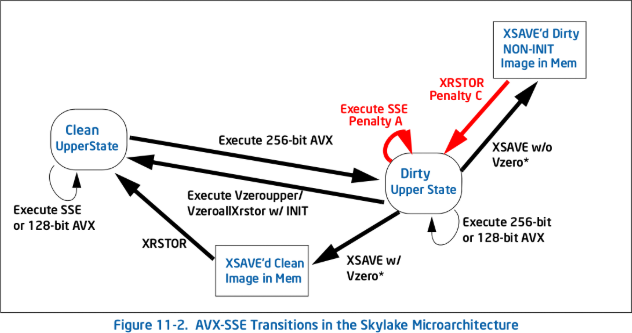

Post skylake, restoring a saved dirty state involves a short penalty, even when no non VEX instructions are executed, and returns to a dirty upper state. Restoring a clean image or restoring with AVX initialized has no penalty and returns to a clean state.